I wrote a short essay on “What If God’s Name Is 01100100?” for the Boston Theological Institute (BTI) Newsletter in 1998. The BTI invited faculties to write about issues facing theological education. I decided to write about the challenges of computer technology and the information highway. The World Wide Web became available in the early 1990s, and I got an email account around 1996. I became fascinated by how technology changed our lives and thinking about God. At the time, there were thousands of websites on religion and spirituality, and Yahoo! located 1457 websites related to “God.” I wrote,

In theological discourse, we have often relied on our analogical, symbolic, and metaphorical imagination. What will theology be like if God’s name is rendered as 011000100, using the binary system in digitization? What will be the attributes of God in our digital imagination? . . .Will we speak of God’s omnipotence in terms of gigabytes, the Holy Spirit in terms of the web of fiber-optic cables, and salvation in terms of Super-antivirus?

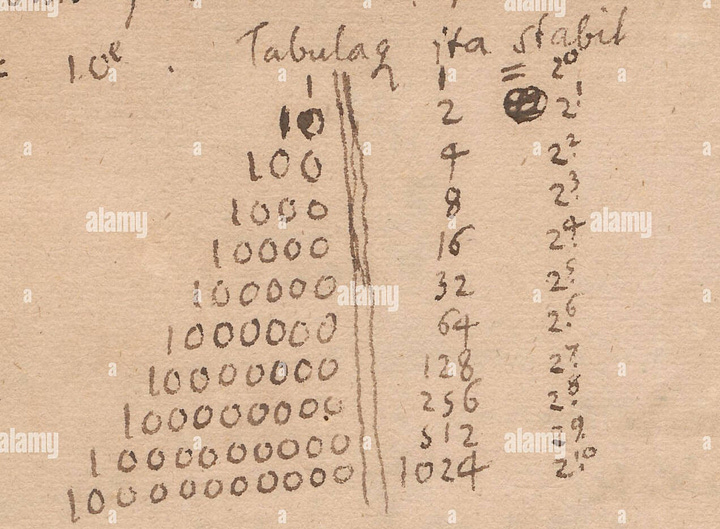

How much the world has changed since then! Later, I learned, to my surprise, that there was a connection between Leibniz’s binary system and the Chinese Yijing (易經). The German polymath and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) created the binary mathematical system, which laid the foundation for computer technology. He showed it to his friend Joachim Bouvet, a Jesuit missionary in Beijing. Bouvet noted the correspondence between the Yijing hexagrams (solid line representing yang and broken line yin) and Leibniz's binary system.

Philosopher James A. Ryan wrote,

The binary system was, for Leibniz, a representation of creation ex nihilo by God, in which each thing is constituted by some permutation of one (i.e. God) and nothing.*

Leibniz and his contemporaries tried to develop a natural theology to explain the creation and the universe. He wrongly assumed that the Yijing hexagrams were evidence of a forgotten Chinese mathematical science and that there were universal principles across cultures and civilizations.

My interest in computers and digital technology continued. In 2011, I wrote a blog entitled “Steve Jobs Might Have Something to Teach Us about Theology.” Steve Jobs, a Zen Buddhist, opted for minimalist design for Apple products and insisted that function and form had to go together. He believed that technology must be intuitive and aesthetically pleasing. I wrote,

I wish theologians had a better aesthetic sense when we create our theological systems. Aquinas’ theology has a cathedral-like design, with transepts and side chapels, flying arches, and vaults. Paul Tillich pictured his systematic theology as a mountain and drew a detailed sketch of the various sections of the work.**

But Jobs’ greatest legacy was captured in the Apple slogan.

When computers were black and beige, the iMac came out in astonishingly Bondi blue, bright orange, and lime green. I urged,

Think different. God is still waiting to come out of the little boxes we have created. Who will write the first iTheology to start a game change?

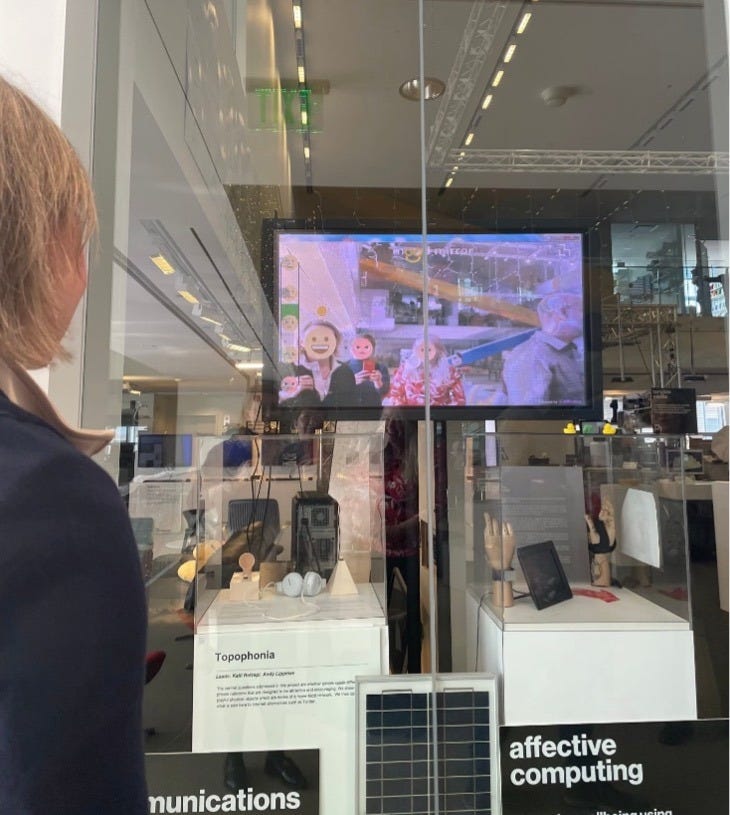

With the AI revolution impacting everyday life, I wanted to learn how AI changes how we think, gather data, process and store knowledge, and teach. I organized a small group of scholars to visit the MIT’s Media Lab in 2022 to learn about innovations in AI, machine learning, robotics, and affective computing research. After the visit, we reflected on the pedagogical implications of the Media Lab and how its physical environment was conducive to collaborative learning, cross-fertilization of ideas, and generation of curiosity and new imaginations.

With group members Tracy Trothen and Boyung Lee, I coauthored the essay, “AI and East Asian Philosophical and Religious Traditions,” in 2024. We found out that Western Christian perspectives often warn against playing God and ascribing human and God-like characteristics to AI. In other words, many still think about God metaphorically.

Chinese philosophy and religious traditions do not imagine the ultimate in anthropological terms. The question “Are they playing God?” does not arise. Therefore, the starting points for asking questions about the relationship between human beings and AI differ.

Scholars of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism argue that Chinese understandings of cosmology, human nature, and society are not incompatible with AI. However, they caution about the impacts of AI and the limits of technology.

Chinese worldviews are more fluid, changing, interconnected, and non-dualistic. Chinese philosophy and religious traditions do not construct dualisms between God/human, mind/body, human/nature, human/machines, and natural/artificial. There are no ontological claims of human exceptionalism. Just as humans have used horticulture, writing, and toolmaking to improve our lives, AI is the latest development following a long line of human inventions.

Popular Daoism believes that human beings can evolve to become transcendent, celestial beings (神仙) through Daoist practices such as alchemy, herbal medicine, and diet.

Just as celestial beings can be seen as an evolved human life, AI can be seen as the digitalization of consciousness to transform human beings into a new “AI species” that can live forever in the data stream.

There seems to be less anxiety about AI and its impact among Chinese scholars, though they also warn against the misuse of AI and want to develop global guidelines about its use.

I can’t help but ask, “Do the Chinese think of God’s name as 01100100?” “What is the impact on AI if we think of God as king, father, or 01100100?”

This brings us to a fascinating question in missiology: Missionaries and Chinese Christians debated about translating the term “God” into Chinese for more than 400 years. Even today, Chinese Catholics use 天主 (Heavenly Lord), mainline Protestants use 上帝 (Most High God), and evangelicals use 神 (Spirit) to translate “God.” It is challenging to reach a consensus because there are diverse understandings of what the term “God” means and how to find an equivalent in Chinese culture, given its vastly different cosmological worldviews.

As we move into a brand-new future shaped by AI and other new technologies, it turns out that the names we use for God and our conceptions about the divine matter.

*James A. Ryan, “Leibniz’s Binary System and Shao Yong’s ‘Yijing’,” Philosophy East and West 96, no. 1 (1996): 59-90.

**Paul Tillich’s papers are housed at the Harvard Divinity School Library. I once saw the mountain picture on display there.

Rosemary Radford Ruether was an artist, actually a painter. She sketched her theological ideas at times. Her concept of women-church included physical space for worship that reflected a non-hierarchical theology.